Environmental Permit Data Service: Phase II

Project Update: October 2022

Our environment is under threat from pollution, overdevelopment and mineral exploitation. Fortunately, in the UK, all of these activities require companies to apply for permits. People are often unaware of applications being made that affect the areas they live and natural sites they care about. It takes time and work to stay informed and be active citizens in our communities. Transparency about these permits is vital for people who care for the environment, whether as a local resident, campaigner, policymaker, researcher, journalist or conservationist.

The Environmental Permit Data Service (EPDS) is a new project to help scrutinise environmental permits in the UK. Environmental Permits set limits on the environmentally harmful activities of companies, like dumping sewage in rivers, incinerating waste, or interfering with local wildlife. The project originated from research commissioned by RSPB in 2019 into missing data infrastructure in the UK environmental sector. In 2020, we did research into various potential users as well as the data itself, and built several prototypes. This update summarises this work and outlines the next phase.

Our vision is for EPDS to exist as an independent data institution, funded by a consortium of environmental NGOs. To fund future work on the project, we anticipate costs of around £100,000 a year, enough to maintain an organiser and a small digital team. If you work with an organisation which might make use of the EPDS tools, or would be interested in talking to us about funding the project, please get in touch!

Background on Environmental Permits

There are a number of different public bodies in the UK that publish data about permits which affect the environment. The Environment Agency, Natural England, the North Sea Transition Authority, local planning authorities, the Scottish Environmental Protection Agency, and other bodies all publish different types of permit, like:

-

Planning permissions

-

Waste operations, installations, and water discharge

-

Animal and plant protections

-

Oil and gas drilling permits

Bringing all these sources together into one searchable database, as well as grouping results by location and theme, will allow organisations scrutinising permits to do it much more easily.

The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) alone has dozens of employees working specifically on monitoring for problematic Environmental Permits. Investigative journalists often look through lots of government data released by different public bodies on different websites, and it would be useful to have tools that bring this data together in one place to allow searching and analysis.

What will people use the EPDS for?

We have identified three major user groups for the EPDS:

-

environmental caseworkers and conservationists

-

policy workers and journalists

-

activists and local residents

Environmental Caseworkers

Caseworkers work for public bodies or in the third sector, monitoring and fighting problematic applications for environmental permits.

-

EPDS allows caseworkers to discover previously overlooked permits or applications

Due to the manual effort currently needed to discover permits and prioritise work, many important permits may be overlooked. These may need attention and intervention by relevant groups. Aggregating permit data into one searchable database will significantly reduce the time it takes for caseworkers to find and prioritise their work. Users will be able to opt-in to notifications alerting them to permits relevant to their work as they are added to the EPDS.

-

EPDS allows faster assessment of permits or applications

Current permit data is minimal and doesn’t provide much context for caseworkers to be able to assess whether the permit requires their attention. Tools to filter and analyse the data as a whole would help caseworkers understand the context for a particular permit or area. They could bring together current and historic permit data, alongside other data such as designated sites, species data and local trends.

-

EPDS facilitates Increased collaboration between interested parties

There are many different organisations and individuals concerned with environmental permits. Without appropriate tools, there may be duplication of work, or different groups working on the same issues in isolation when they would benefit from collaboration. Easy-to-use networking tools to help caseworkers from different organisations understand when a particular case might be of interest to multiple groups and reduce costs of collaboration.

Policy Workers and Journalists

-

EPDS allows faster search and analysis

Manually having to search different websites and analyse the data presents a burdensome workload for researchers and journalists. Adding tags and categories to the data would allow journalists and policy workers to reveal trends and patterns of permits. They would also make the data easier to search and filter. Custom dashboards and applications to help understand and explore the data in context can also be created. For example, users could search for a list of solar farms in or near Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs) and have the data displayed visually.

-

EPDS helps with identifying case studies that meet certain criteria of interest

Many organisations are only interested in particular kinds of permit (e.g. ones to do with oil and gas extraction, or which threaten certain habitats). Being able to search and filter permits would allow these organisations to see only the data of interest to them. This would make prioritisation of work and collaboration between organisations easier.

-

EPDS provides data for visualisation to make reports more impactful

Most journalists and policy researchers will not be technically competent at data visualisation. However, visuals are invaluable tools for disseminating information. We have been using Google Studio to provide basic graphs and visualisations for dashboard data. Such visualisations can massively reduce the work of researchers and journalists who may not have the technical skills to produce visualisations on their own.

Activists and Local Residents

-

EPDS facilitates discovery of new permits

Local citizens and community organisers need to be aware of changes to their communities in a timely manner so that appropriate action can be taken. Campaigns take time to organise, so the sooner information is available, the better. Location-specific search engines and email alerts would allow the general public to find and stay aware of permits in their local area with much less effort than they would currently need to expend. A map-based interface to explore the data is also being developed to help surface data based on geographical area.

-

EPDS encourages increased civic engagement

Many citizens don’t engage with local governance, but might if information was easier to access and taking action was more convenient. Tools to help the general public or local groups to find relevant data and to intervene in issues they care about. For example by emailing their MP or finding groups campaigning in their area.

-

EPDS facilitates community organising

Finding other affected parties to join your movement is critical to its success. Activists need simple yet effective tools to organise their communities to take action. Social engagement tools will help interested parties find one another and share relevant information. Tools to provide graphics and content to support social media campaigns around environmental issues at critical moments.

There are many opportunities to use this data in impactful ways, create high-quality infrastructure that can reduce the costs of working with this data, and open up the sector’s imagination as to what might be possible. We want to give people the tools to understand the aggregate effect of environmental policy on the country and its ecology for the first time.

Other environmental NGOs (Woodland Trusts, Plantlife, Unchecked UK), were excited about the possibilities of this data being put to use, and collaborating around it. John Lubbock, an investigative journalist and open data expert, will be leading the next phase of the project, which will require engagement with other organisations who could either use or potentially fund further work on the EPDS.

The State of the Project

The Environmental Permit Data Service began as an idea in 2018, and while the discovery phase of the project has been completed, there have been a number of Covid-related interruptions which have delayed the project. The project began as a conversation between the RSPB and Ed Saperia. Ed put together an advisory board and technical team, and the discovery phase was funded by a grant from the RSPB. This phase included:

Work so far

-

Surveying government and NGO websites, to understand the data that is currently being published. See Appendix 1 - Sources for details.

-

Carrying out assessments of a sample of the datasets that we found, to understand the properties of that data.

-

Writing software to use the data, to understand what the data is like to use in practice.

-

Interviewing case workers at the RSPB about their work and how technology could assist them in working more efficiently and producing a report on their needs.

-

Reviewing the prior research on caseworkers’ needs and discussing the report with Andrew and Carrie from the RSPB.

-

Interviewing senior stakeholders both within the RSPB and at other environmental NGOs. See Appendix 2 - Interview Participants for details.

-

Writing software to attempt to meet the expressed needs, and seeking feedback on the utility of the technical possibilities that we were uncovering.

We built four prototype tools in order to help us understand the technological possibilities for working with this data:

-

An aggregator

-

A search-and-filter service with a map interface

-

An email alerting service

-

A dashboard to support specific policy investigations

1. Aggregator

The basic goal of this project is to aggregate public data which is available on different websites so that it can be found in one place. To do this, data is scraped from a number of different websites so that it is searchable in one place. Aggregation is important for almost all use cases, and so this is a valuable shared component.

2. Search-and-filter

We have built a prototype tool at http://dev.epds.opendataservices.coop which offers a record-based interface and a map search interface to the data.

Record-based interface

Best-known on websites such as booking.com, a record-based search-and-filter interface allows users to gradually refine a query until they find the record (or collection of records) that they’re looking for.

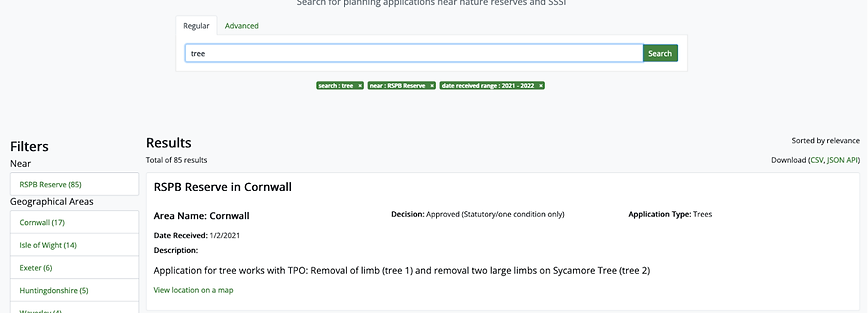

Of particular interest are filters that draw on geographic information, such as “within a Site of Special Scientific Interest” or “near an RSPB reserve”. For example, you can find applications relating to trees near RSPB reserves in 2021:

Map-based interface

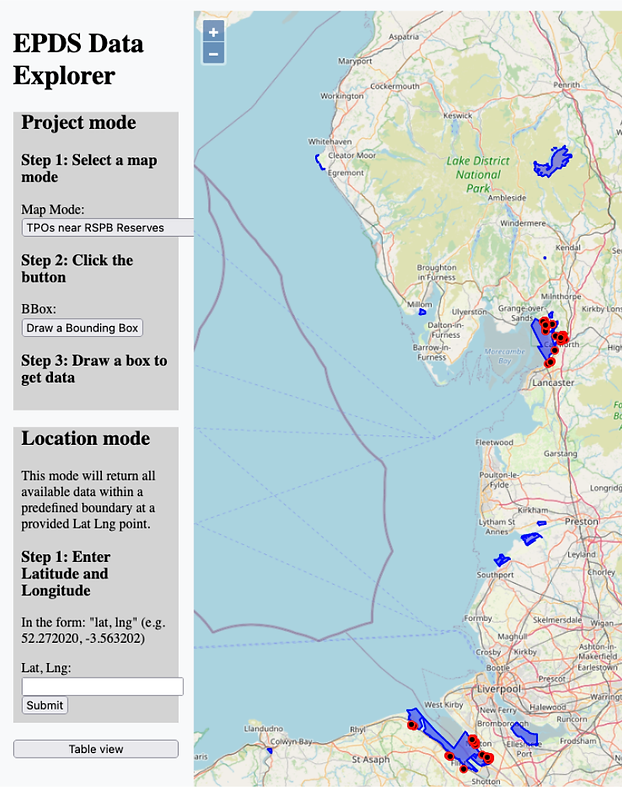

The map-based search allows users to use pre-defined data sets (such as “applications to alter trees subject to Tree Protection Orders near RSPB reserves) by drawing on a map. For example:

The “table view” shows details for the results that are shown on the map.

Data about permits and locations, when combined, can be used to create powerful tools that don’t require users to have high level technical skills.

3. Email alerting

We built an email alerting service which checks for new planning applications relating to trees subject to Tree Preservation Orders (TPOs) that are in or near RSPB reserves or Important Bird Areas (IBAs) each day, and sends an overview of the information to interested parties to review.

An email alerting service can be created using this data, as long as the criteria for something being “of interest” can be clearly defined. Creating useful categories and definitions will be key to the success of this feature, and will be a priority for further work.

4. Dashboard

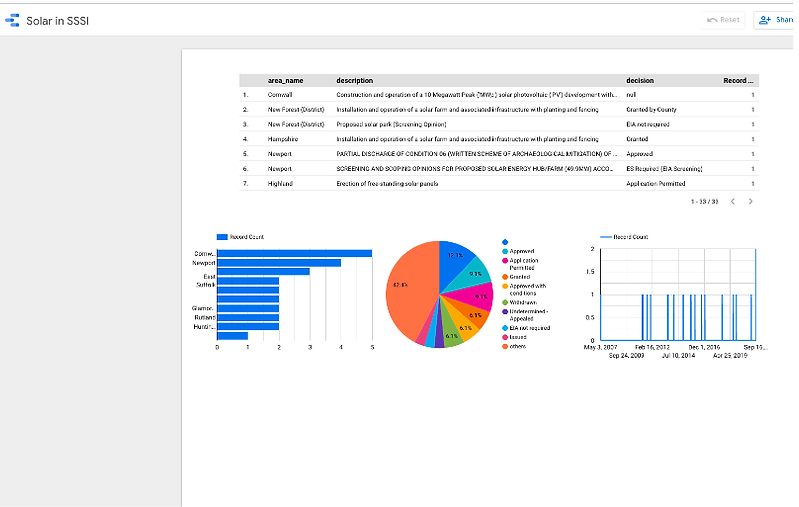

Alongside this, we have been experimenting with the possibilities using Google Data Studio to understand how a visual-first presentation of filtered data may be helpful. In the below example, we’ve:

-

Generated a list of all planning applications that are in or near SSSIs

-

Run a query on the data set to get a candidate list of planning applications that may relate to solar farms, because they have some combination of the terms “solar”, “PV” and “park” or “farm”.

-

Manually, in a spreadsheet, tagged these as “relating to a solar farm development” or not.

-

Used some stock Data Studio visualisations to give an overview of the data set; these are interactive, so a user could click on (for example) Cornwall to see just the applications in that area, and the breakdown of approvals/rejections.

Detailed analysis of the data is where data quality issues become most evident. By using the database to filter out irrelevant details, the manual / machine-assisted process of preparing the data for analysis is quite straightforward.

While proof of concept has been established, much more work is needed to build out the technical capabilities of these tools. We plan to use any future funds to concentrate on adding features that would make the project as useful as possible to those stakeholders who might use it.

Roadmap

Right now, there’s a lot of potential, and some valuable - but rapidly depreciating - assets: a server, some prototype software, and a database that’s only being maintained on a best-effort basis.

In the future, there could be a vibrant community of people using permit data to underpin a wide range of environmental protection activities - some directly, but more as the connecting factor across a range of other types of data. This community could include environmental NGOs of all sizes, organisations with an interest in protecting nature, individual members of the public - and people we haven’t thought of yet!

Collective Ownership

This community would own some core infrastructure that allows them to use the data, and would be able to advocate for improvements to the data at source. They would find new ways to collaborate, using the data to understand common interests and concerns.

In the course of our research, we generated a lot of excitement - everyone that we spoke to could immediately see how this data could be useful. Building on this, alongside the board that Edward Saperia has already assembled to develop this work, a community could be brought together to guide this work and to develop it.

Building Community

Building and maintaining a community is a time-consuming task that needs to be properly resourced, but that offers substantial returns when done well, and as part of a coordinated approach to driving a particular initiative forwards.

Supporting the growth of the EPDS community, would likely involve organising regular calls among people who might be interested or who might contribute in some way, providing spaces for discussion of ideas and building up relationships, and regular circulation of work that’s been done to canvas for further participation.

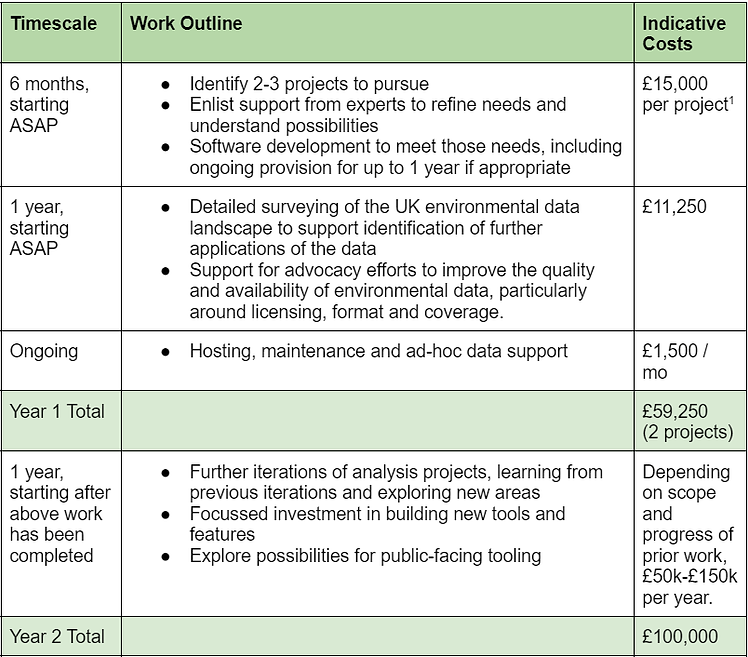

Over the next year, the focus should be on three areas:

-

Get permit data into real-life use where it is relatively straightforward to do so, and worth the cost. Then, learn from how these pilot projects are going - and improve from there.

-

Building a community around the data, and getting them excited about what can be done.

-

Establishing the guiding principles of managing this common resource among everyone interested in the work.

Benefits of Digitalisation

In general, eNGOs seem to be quite early in their digitalisation journey: although a lot of work is conducted online, it relies heavily on analogue metaphors (files, forms, etc) rather than being digitally-native. Creating a digital platform as an integrated part of the work of eNGOs could dramatically improve the quantity and quality of their work. There are a lot of exciting opportunities, and permit data could be a way of unlocking digital ways of working within the sector.

Right now, anyone trying to do a project using this data will have to carry out a similar set of first steps in order to start work: obtaining data from the various places where it’s published; extracting common fields such as description, date and location; and carrying out basic deduplication and augmentation. As a result, the greatest overall value can be gained by reducing the cost of getting started, which can be achieved by providing that service once, for use by all.

This encourages experimentation: an investigation of an idea becomes much simpler, and there are more examples to inspire creative thinking. Moving from experimentation to a useful application becomes cheaper too, because the groundwork that anyone would have to do, has already been done.

This is common to almost any data ecosystem: data that is technically available goes unused because the effort required to work with it exceeds the available time and resources available to investigate its utility.

How you can help

Working with the EPDS to improve environmental data has a clear business case for the organisations involved in this study:

-

It offers cost-saving through automation of manual processes.

-

It opens up new possibilities for areas of work that were infeasible due to volume or complexity of data.

-

It offers the potential for the public to be more engaged and mobilised on more local issues, rather than exclusively at critical moments.

-

Through simplification, it opens the space for imagination of new ways in which this data could be used.

Core Funding

A project like EPDS will require some regular funding in order to continue running basic infrastructure - the components that are shared between all applications that use the data. Keeping servers online, updating interfaces as underlying websites change, and dealing with the evolution of software all have costs.

A key sponsor to cover those costs would send a strong signal to others that this was a long-term proposition and would also be likely to offer some security that it was worth investing in.

Funding for Projects

With our initial investment of £60,000 from the RSPB, we have been able to build the groundwork in developing this idea into a workable proposition. As we continue to work with the aggregator and existing tools, new features, analyses, and uses of the data are likely to be surfaced on a regular basis. Each of these might attract project funding from newly interested sponsors - either funders who might be willing to fund potentially impactful projects, or NGOs who see a specific place in which a new use of the data helps them to achieve their goals.

These organisations could fund development across the project, although the long-term maintenance costs of any new features should be taken into account.

Commercial Services

There are some potential opportunities to offer services on a commercial basis. This is most obvious when there is a clear labour saving which can be shared across organisations. Data augmentation, assurance and cleansing are all examples of this.

Open Data Standards

Our aim is to work towards better open data standards. Data published by different bodies is currently lacking standardisation. The UK government has a National Data Strategy which includes general commitments to better standardisation of public data. The EPDS could potentially have a voice in this conversation.

Open data standards reduce costs and improve the value of data, and their implementation helps organisations understand their own data better. In this case, open and standardised data about permits could be put to use by a range of organisations, in order to help better understand the environment around them.

Open data advocacy is a well-established practice yielding significant results across the globe, relying on:

-

Coherent, outcomes-based arguments

-

Consistent advocacy from respected individuals and organisations making reasonable but ambitious asks

-

Ongoing work to reduce costs and risks around high-quality open data publication, through standards, guidance, training and technology.

By working towards high-quality open data, the long-term sustainability of data-driven approaches to environmental accountability can be improved.

Team

-

Interim Director Edward Saperia

-

CTO Robert Redpath